My two criteria for a new solution to help my hearing and comprehension were met:

- probable significant improvement

- little risk of balance and vertigo problems

There was a third requirement, given that I could not afford the great expense of the implant itself, the surgical fee, the hospitalization fees and the rehabilitation fees. More on that in a moment.

A little help from my friends

I have no family members, no acquaintances with a cochlear implant. I asked medical and audiological personnel for references. Four people kindly agreed to discuss with me their own experiences.

Naturally, I was referred to people who experienced at least a modicum of success in using a cochlear implant. Keeping this in mind, I heard for myself the limits these people experienced. They ranged from someone whose implant completely changed his life (for the better) to someone who needed her husband to help out during telephone conversations. In short, cochlear implants result in a range of experiences. I asked each person my “bottom-line” question: Given what you know now, would you do it again? 100% in the affirmative.

I already knew from reading that cochlear implant results vary tremendously. The main benefit to me of discussing with these kind people was the positive emotional energy that they imparted. If my two primary decision criteria were logical in nature, my exchanges with other users helped me to feel good about my decision.

The cochlear implant

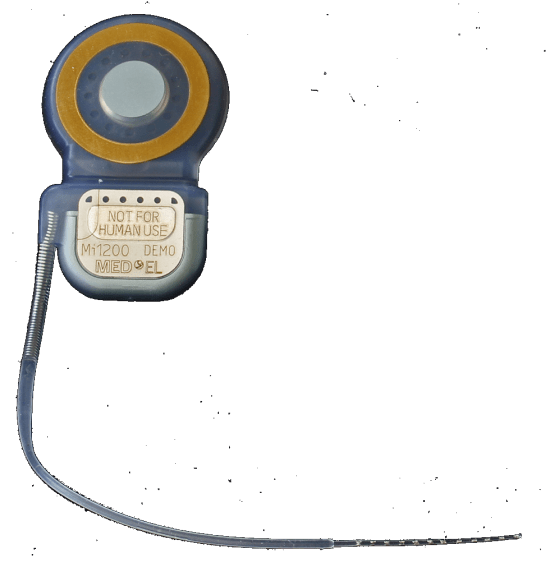

For those who are not familiar with the cochlear implant, I will briefly describe it. The device consists of two main components.

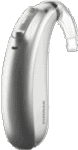

An external component has one or more microphones, a digital signal processor and an antenna. Multiple microphones allow for a certain sense of directionality in the sound captured. The digital signal processor converts the analogical signal from the microphones into digital signals. It transforms those signals to enhance their comprehensibility by the brain. The antenna transmits the signals through the skin to the internal component of the device. It is held in place by a magnet that attracts an internal magnet.

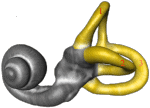

The internal component consists of a second antenna, another signal processor and a set of 20 some-odd wires (the number varying according to the model). The second antenna is inserted by a surgeon under the skin, a few centimeters above and behind the external ear. The processor takes the received signals and distributes them to the various wires. This electrode is connected by the surgeon to the cochlea.

Thus, the cochlear implant completely bypasses the outer and middle ears. It provides an alternate channel from the external sounds to the cochlea, whence the signals stimulate the auditory nerve.

Choosing a device

The hospital where the implant was to be done offered a choice of three brands of cochlear implants. Naturally, my very question was which one gave the best results. The simple answer was that no single brand was better than the others, from a hearing and comprehension point of view.

Many of the devices could be powered either by replaceable batteries or rechargeable batteries. I preferred to recharge, so that excluded certain models.

There are essentially two styles of external components: a simple “button” that is relatively thick; and a combination of behind the ear component linked by a wire to a relatively thin “button”.

Since I already wear a behind-the-ear hearing aid and have no difficulty in using it with my eyeglasses. I did not think at the time of the use of surgical masks. It turns out that the mask is always getting tangled in the device, but that’s no big deal.

On the other hand, some feel that the positioning of the microphones in the device near the external ear would be slightly better than the positioning on the thick button. That made sense, although I saw no objective evidence to support it. Finally, there was the question of compatibility with external devices, like telephones and computers, that was important to me.

Other criteria that could possibly have helped decide among the various models and brands, but they were not important to me.

When I finalized the order for the implant, the surgeon told me that a particular model was better suited to my particular pathology, with a build-up of calcium around the round window area of the cochlea. Since he wanted to use the same brand as the one I had already decided to use, everyone was happy.

Paying for it all

Happily, I live in a country where health insurance, although private, is mandatory for all residents. Disability insurance is mandatory for anyone with a revenue. The health insurance covers 90% of the surgeon’s and hospitalization costs. The disability insurance covers the cost of the cochlear implant, the audiologist and a certain number of speech therapy sessions. In short, it would all be affordable.

Getting rejected by an insurance company is an issue I see frequently in forums about hearing. I am glad to live where insurance companies treat their customers as basically honest, as opposed to that country where they seem to treat customers like crooks, where the default mode is to reject any claims.

There were a few snags to be worked out in my case, but all was done in a good spirit and expeditiously.

A little publicity

The hospital managed a video series highlighting various of its activities. It turns out that the department handling cochlear implants was to be featured just at the time I was to undergo the operation. So, I was asked if I were willing to participate in that video, with an interview before the operation; a filming of the operation itself; and filming the session when the implant was first activated.

Having benefited from my discussions with other patients, I was pleased to be able to contribute to the diffusion of information about cochlear implants. I agreed and the video is now available to the public.

The video is in French. For those faint of heart, you might wish to skip the part showing the operation itself, from 2:59–3:27.

The Operation

Running a hospital and scheduling the use of the operating rooms requires considerable agility. It’s fine and good to schedule an operation for a certain time, but emergencies do arise, causing changed scheduling of elective surgery. On top of that was all the uncertainty associated with handling the pandemic in 2020.

I was called the day before the scheduled operation telling me I was expected at 6:00 the next day. Concerned about the risks of surgery—however small they might be—I showered that evening using an antiseptic soap. I showered again the next morning with the same soap. And the few hours of sleep I had in between were on sheets freshly washed using an antibacterial product. Maybe I exaggerated, but the additional effort and cost were insignificant compared to the possible downside of an infection.

It turns out the operation did not start until 10:30. You can see some of the details in the video above.

When I finally awoke it was early afternoon. By the time I returned to my room it was after the normal lunchtime, but I had the right to some chicken broth.

My wife was able to visit me in the afternoon—no small feat in a hospital hyper-conscious of the risk of COVID-19 infection. It just had to be organized in advance so she had a pass.

Unlike my previous experience in waking after an ear operation (recounted here), things went quite well. I had a minor headache. My throat was a little sore, presumably from the breathing tube put down my throat in conjunction with the general anæsthesia. It seems that some people suffer from some form of reflux under anæsthesia and this tube helps to reduce the risk of vomit clogging something. In any case, I had no such problem.

Finding a comfortable position to sleep that night was a little tricky. I slept on and off but did not have any major problems.

The next day, I was scheduled for a scan to make sure all was well, followed by my discharge. I use the word “scheduled” loosely, as I was ready for the scan at 8:00, but they did not get around to doing it until 15:30. The surgeon checked the results and I was on my way home by 16:30.

It would be several weeks before the implant would be activated, during which my major job was simply to heal.