As I am now facing imminent corrective surgery for my cochlear implant, my thoughts have lingered on the question of how well does a given surgeon practice surgery. These thoughts center around three topics:

- Surgery as a complex system

- Biases in reports on surgeon “quality”

- Regression to the mean

Surgery is a complex system

It is pretty obvious that anyone undergoing surgery is participating in a complex system, rather than being solely dependent on a particular surgeon’s skills. All of the actors in the system contribute to the quality of the outcome. Does the anesthesiologist select the most appropriate methods? Is the anesthetic under careful enough control? What percentage of the surgical assistant’s actions are sufficiently timely and accurate? How clean is the operating theater? How well rested is the patient? Has the patient taken care to be hygienic and prepare for the surgery with appropriate vaccinations? And yes, has the surgeon selected the most appropriate method? Does the surgeon execute that method accurately enough? Is even the “best” method any good at all?

And those questions just takes into consideration the more immediate issues. Does the surgeon have family members whose cares dominate the surgeon’s thoughts? Have the patient’s acquaintances created an atmosphere of negativity around the patient? And so forth….

As with any complex system, many of these factors influence other factors, It is impossible to isolate single causes of an outcome. Nor is it likely that factors can be correlated with outcomes in a simple, linear fashion. Instead, there are probably tipping points in those correlations. Up until a certain point, the combination of factors may seem anodyne. It takes but a slight change in one factor to trigger a cavalcade of mishaps.

As a complex system dependent on so many factors or such variable and often unclear dependencies, we can hardly speak of surgery as causing successful or unsuccessful outcomes. Instead, we must speak of the probabilities of outcomes.

My first surgery was a stapedectomy. At the time, the surgeon told me that 95% of cases showed improvement; 4.5% of the cases resulted in no significant change in hearing; and the remaining .5% resulted in a worse condition. Those statistics sound great for a population as a whole. But what do they mean for individuals? Since I belonged to that .5%, I can tell you that the statistics help to convince yourself that you did not make a stupid decision in going ahead with the surgery. Anyway, it’s best to focus on the next steps to make the best of a situation and try to improve, rather than to focus on past decisions that led to unfortunate outcomes.

Biases about surgeons

We all know that surgeons are surrounded by a mystique. That mystique is fed and reinforced from many directions. One of the most important effects of this mystique is the creation of biases in the minds of patients.

One of the most important biases is the classification of surgeons into two categories: butchers and miracle workers. We are inevitably led to such thoughts because we seek to make decisions about which surgeon to use. Those decisions are all 100% or 0% type decisions. Either you use a given surgeon or not. You normally cannot use one surgeon for75% of the surgery and another surgeon for the remaining 25%, as a sort of bet-hedging. In short, we seek simple answers to complex questions.

In our attempt to find the “right” surgeon, we ask around for opinions and recommendations. If a friend or family member tells us of a “miracle worker”, we are, of course, very favorably biased in favor of that surgeon. But, in all likelihood, we have merely replaced our own biases by someone else’s. Was that assessment as “miracle worker” based on a single case, or was it an assessment based on 20 years of experience performing hundreds of operations? It is almost certainly the former, since statistics for the latter hardly ever exist.

And what happens if we undergo surgery by a miracle worker where is outcome is not positive. The surgeon’s mystique is likely to lead us to the conclusion that the fault is in ourselves, or in our stars, but hardly due to the surgeon.

Another important bias is the unwillingness to bad-mouth someone. If the outcome was not favorable, many people hesitate to put the blame on the a single cause—we are too nice or circumspect to do so; we are happy to extend the benefit of a doubt (and rightly so).

Regression to the mean of surgical performance

Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky (among many others) have written about the problem of not recognizing the impact of regression to the mean. They recount the story of the how the air force trainer would severely berate pilots who performed poorly on a flight. In their next flights, those pilots inevitably performed much better, so the trainer was convinced the the tongue-lashing was very effective as a technique. In reality, however, the trainer’s methods have little to do with the performance on individual flights. In any case, the next flight was almost certain to be better. This is the phenomenon of the regression to the mean.

Thinking about surgery in these terms can be instructive. Let’s imagine a hospital where the outcomes of a certain type of surgery are grouped as follows:

- In 75% of the cases, the outcomes are pretty good

- In 15% of the cases, the outcomes are really excellent

- In 8% of the case, the outcomes are not so good

- And in the remaining 2% of the cases, the outcomes are quite bad

Suppose your friend tells you that he heard of a recent case where Dr. X performed wonders. In other words, that case was one of the 15% of the cases with an excellent outcome. What is the likelihood that Dr. X’s next surgery will also be excellent? It is only 15% of the time. In other words, the next case, in 85% of the times, will have a poorer outcome!

Now, let’s suppose that friend heard about the case where Dr. Y’s effort resulted in a very poor outcome. That is one of the 2% of the total cases. So, there is a 98% probabilitiy that Dr. Y’s next case will have a better result.

My choice of a surgeon

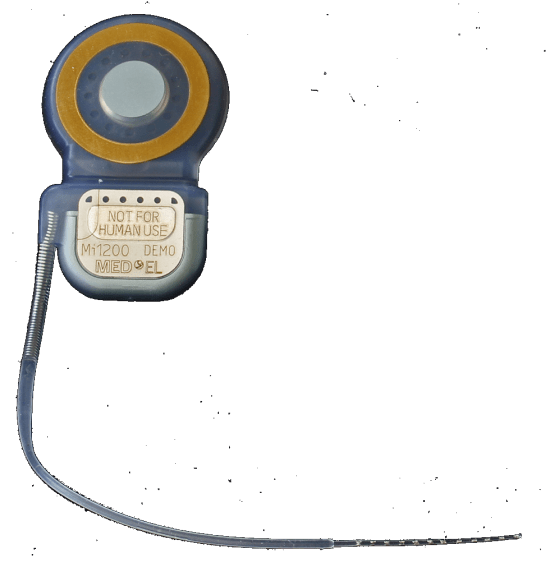

I underwent cochlear implant surgery about 2 years ago. The result was a significant improvement of my comprehension of human speech, but the result was far from the potential of cochlear implants.

It turns out the electrode was not positioned optimally. It got stuck on a calcium deposit and so was not married to the cochlea as well as it might, at the place. The result is a sound dominated by sibilance.

I suppose some people might blame the surgeon for this mishap. But I find this largely irrlevant to my choice of a surgeon. As far as I am concerned, that surgeon is the only person to have examined my cochlea up close, and that has to be an advantage.

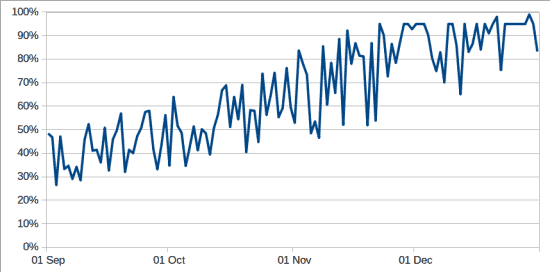

In any case, with some luck the surgical system will regress to the mean and I will end up with an improvement. I’ll let you know how things turn out.