Most of us probably cannot remember when we were one or two years old, first learning to speak. In my mind, learning to hear and comprehend via a cochlear implant resembles learning a new language.

Do you remember your first lessons in learning another language, when you listened to a conversation in that language? If you are like most of us, You couldn’t make heads or tails of the speech. It sounded like gibberish.

However, as you learned some basic principles of that language, as you performed exercises and, especially, as you tried speaking and listening, you gradually gained in comprehension and your facility in using that language.

So it seems to be when you first have a cochlear implant installed. Unless you are one of those miracles who understand everything right away, a cochlear implant allows you to hear sounds, but you comprehend few of those sounds.

What you first hear

If you were adequately prepared for the experience of getting a cochlear implant, you had been told to expect voices to sound “robotic” or “electronic”. That’s not at all how I would describe my own experience.

At first, I was at a loss to describe what I was hearing. But I quickly found a vocabulary to express what I was hearing. Sounds were whooshing. It was as if speech were windswept. In many ways, voices sounded as if people were whispering, albeit those whispers were at a normal loudness and not at all soft.

On top of that was a whole series of sharper sounds punctuating my hearing. It took me even longer to find a way to express these sounds. Imagine that the person talking to you is also balling up a piece of aluminum foil. I was hearing that crinkly, metallic sound of touching the foil.

For a while, I was convinced that the metallic sounds were due to some defect in the device or some problem of configuration. How could I possibly be hearing all these noises while sitting in a perfectly calm office? I was disabused of this idea through a simple test. The audiologist led me to one of those highly insulated rooms in which hearing tests are made. And lo, all those metallic sounds stopped.

I couldn’t believe how noisy the world had become during the previous decades of diminished hearing.

Two ears, but how many sounds?

I was long accustomed to hearing with only one ear. But now I had two ears hearing things. If someone would say a word to me, I would hear two entirely different sounds. I was not yet capable of fusing the inputs from my left and right ears into one sound.

When the audiologist would ask me where I heard things, my answer was that the sounds from my left ear appeared to be localized in the center of my head, whereas the sounds from my right ear were localized in the right ear.

For the first few months, the differences in sounds between the two ears and my inability to hear and understand them as a single sound, led me to consider the sounds from the cochlear implant were distracting me from comprehending speech.

This belief was perhaps hindering my rehabilitation. After a few months, a speech therapist demonstrated to me, via some simple tests, that I comprehended better when I used both ears than when I used my left, hearing aid ear, alone. Since then, I’ve tried to put a more positive outlook on the strangeness of what I hear. Keeping a positive attitude and having that attitude reinforced by others is very important to my hearing rehabilitation.

Exercises

I live together with my wife in a house somewhat apart from the neighbors. I don’t have an office where I meet colleagues. And my social activities have been strictly limited due to the confinement and social distancing we practice to limit the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

So, I cannot depend very much on chattering away with different people all day long as a way of accelerating my hearing rehabilitation. Doing exercises has become all-important.

Hearing exercises are unlike academic exercises

The other great frustration with hearing exercises is reaching a blockage where there is simply nothing you can do to improve. For example, a common type of exercise hinges on understanding the difference between two consonants or vowels. In my current state, I am utterly incapable of distinguishing an “m” from an “n”, and distinguishing a “d” from a “g” is really hard. No matter how many times I redo exercises, my success rate with “m” and “n” seems to be random. There is nothing I can hook onto, no trick that allows me to master the skill. You can imagine it is not easy if one cannot distinguish between “ma’am” and “man”.

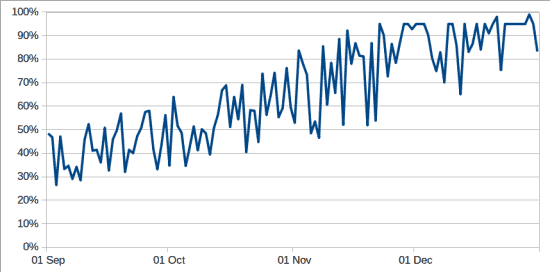

I find the hearing exercises to be very different from the academic exercises I used to do, like learning the multiplication tables or the declensions of Latin nouns. For those exercises, you could reach a point where the knowledge was acquired and there was no going backward. With my hearing exercises, I could get a 90% correct rate for an exercise, but two weeks later get only 50% correct two weeks later. So, understanding what you hear is not a cognitive skill like knowing the rules of algebra. Perhaps a better analogy would be with stock market prices that fluctuate widely from hour-to-hour and day-to-day. It is only after a year can you see a definite trend.

Challenging exercises

Currently, my favorite exercises involve trying to comprehend complete sentences or short conversations. In my current state, the first time I listen to a recording I am lucky to understand one or two words. I replay the phrase, listening for the sounds that do make sense to me. I play it again, trying to imagine what word could possibly fit the pattern of sounds I think I hear. Once I convince myself I have understood a word, figuring out the neighboring words becomes much easier.

A simulation of repeating an exercise and increasing comprehension with each repetition.

In this sense, the exercise resembles a crossword puzzle. Some clues are easy. Those answers fill in letters for the terms that are more ambiguous. You make a few guesses and you start to see a pattern to the whole. Often, there is a very difficult section with one or two clues that you simply cannot solve. Similarly, after playing a sentence five, ten or even fifteen times, I can usually figure out what is being said. But sometimes there is a word whose sense I simply cannot detect. If I were in a real conversation with someone, I would simply ask for clarification. But in my exercises, my solution of last resort is to turn on my hearing aid and listen to the sentence with both ears. Once you know what is being said, everything becomes crystal clear. You hear everything where, just a minute ago, it was all nonsense.

This sort of exercise is fulfilling because you have a clear way of seeing the progress you make. Furthermore, there is almost always a little bit that is still not clear, showing you that you still have more work to do, something else to learn and to improve.

More basic does not mean easier

Paradoxically, the simplest exercises are sometimes the most frustrating. One exercise consists of listening to three tones, as if someone had played three notes on a piano. The idea is to identify which tone is different from the other two.

As someone who has played a variety of musical instruments, especially between the ages of eight and twenty-five, the inability to distinguish two different notes is extremely frustrating. Worse is that I can do nothing about this inability. This is similar to the problem of confusing “m” and “n” to which I referred above.

On the one hand, I have been told that my inability is due to the limits of cochlear implant technology. Imagine, for example, that you had to represent the 88 different notes on a piano with a palette of only 22 detectable notes. Thus, do, di, re and ri all sound the same. On the other hand, you can hear the difference between do and mi. Imagine hearing the lyrics, “Do, a deer, a female deer” sung in a monotone.

I don’t know what to make of people with cochlear implants who say they fully appreciate music. Setting aside the philosophical question of how to compare perceptions by two different people of the same sense data, I sometimes have the uncharitable thought that these people are simply tone-deaf. I know that I am, at least in my right ear.

There is another exercise in which you are supposed to identify which musical instrument is playing a snatch of a tune. I am a whiz at identifying the snare drum and even the xylophone. I am not too bad at identifying the breathiness of the flute. But, for someone who used to be able to easily distinguish a viola from a violin, it is extremely hard on my self-esteem to fail to hear the difference between a clarinet and a ‘cello. And worst of all, none of these recordings (aside from the snare drum) sound at all like the instruments supposedly being played. Will this utter lack of appreciation evolve? I dearly hope so.